Architecture

Liveable Cities and Desire Lines: Urban planning perspectives from Denmark’s Bicycle Ambassador

The focus on re-establishing more liveable cities continues unabated. The primary problem however is that 85 years of traffic engineering revolving around the car has failed miserably. It’s time for modern thinking, and good design can help.

Historically, streets were human spaces, so why don’t we still design them in accordance with the desire lines of their citizens? The following talk, given by Mikael Colville-Andersen, makes the case for using basic design principles instead of engineering as the surest route to developing thriving, human-centred cities.

Colville-Andersen is an urban mobility expert and CEO for Copenhagenize Consulting. He is often called Denmark’s Bicycle Ambassador but has learned the hard way that this title is a dismal pick-up line in bars.

Colville-Andersen and his team advise cities and towns around the world regarding bicycle planning, infrastructure and communication strategies. He applies his marketing expertise to campaigns that focus on selling bicycle culture and bicycle transport to a mainstream audience as opposed to the existing cycling sub-cultures in particular with his famous Cycle Chic brand. Colville-Andersen gives talks around the world about bicycle culture, design, and social media.

Those who are familiar with TED talks will know that they are synonymous with quality and intelligent commentary. My favourite bit of this particular talk begins at 5:27 and considers Copenhagen’s approach to the “desire lines” of its citizens. After watching this segment, just think about how other cities around the world might be quicker to punish (rather than observe) their citizens in cases where they routinely flout the law – which approach do you suppose is better?

Space for cycle lanes – it can be found!

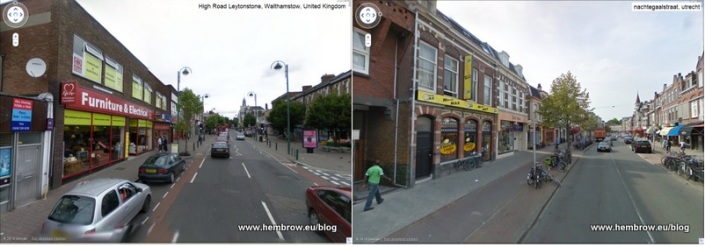

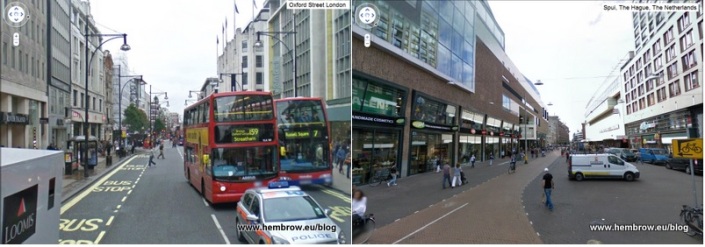

Whenever I tell people about my dream of having some decent cycling infrastructure in the UK, I am frequently met with the same point about there not being enough space on British roads. The general feeling is that roads are already too narrow, and that there simply isn’t any room to accommodate the type of segregated cycle lanes that work so well on the continent.

In opposition to this, I would like to present you with a group of photos taken from Google Streetview. In the left column you have shots of roads/junctions in the UK, and in the right column you have almost identical shots of places in The Netherlands. The point of the side-by-side comparison is to show how space is used differently, and how the Dutch so sensibly choose to separate pedestrians and cyclists from cars and HGVs. The streets are so similar that they could almost be before and after photos…

In each case, the cycling provision in the UK is rubbish or non-existent, while that provided on a similar street in The Netherlands offers a far superior cycling experience. Of course, if cycle lanes were better then more people would cycle, and if more people were riding bikes then there would be fewer cars on the road and so less congestion and less pollution. Everyone benefits, right?

The following video explains how the Dutch got their cycle paths, and how their cities made the transition from being car-centric to being more bicycle friendly.

What the Dutch have achieved is truly remarkable, and this is why I always hold them up as the best example for the UK to follow. They are the only country in the world able to boast the fact that more than a quarter of all their journeys are made by bike, and it would be my dream come true if we could achieve this feat in the UK.

Related articles

- Making cycle lanes safe (cyclingnelly.wordpress.com)

- Crosspost: Cyclists and pedestrians as ‘hazards’ for motorists. #wordlturnedupsidedown #takecaregtrmcr (manchesterclimatemonthly.net)

- No, it’s not the narrowest cycle path in Britain! (cyclingnelly.wordpress.com)

- Only 10 fines for illegal cycle lane parking (belfasttelegraph.co.uk)

A post about roundabouts (of all things)

Video Posted on Updated on

The Dutch have done it again; as usual paving the way with an innovation that is as beautifully engineered as it is practical. Constructed between Eindhoven and Veldhoven, the new ‘hovering’ roundabout separates bicycles from the motor vehicles below, harmonising high-functionality, aesthetic appeal, and plain old-fashioned genius.

My initial reaction of awe quickly turned to irritation as I realised that I don’t live in The Netherlands any more. This morning’s emotional roller-coaster took yet another turn as jealously turned to joy when I caught wind of plans for more conventional Dutch-style roundabouts to be trialled in the UK: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-22347184

For those of you who are unfamiliar with how Dutch roundabouts work, check out this brilliant video from our friends at NL Cycling: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XhqTc_wx5EU

Dutch roundabouts are intuitive to use once you understand how the shark-teeth markings on the road indicate priority, and there’s really nothing to it. Roundabouts can be pretty dangerous and intimidating places for cyclists in the UK, but in The Netherlands they are a breeze. Transport For London (TFL) has raised concerns that the Dutch design might reduce the speed of motorised traffic. Personally, however, I don’t see that as a cause for concern, but rather yet another benefit of a concept that prioritises the most vulnerable road users.

If the UK is realistic about meeting emissions targets, combating sedentary lifestyles, and generally improving the nation’s health then a great way to do this is to incentivise cycling by introducing measures to protect and prioritise people on bikes. It frustrates me when such a simple and elegant solution to so many of our country’s problems exists within tantalising reach but remains obstructed by a system that perpetuates antiquarian notions of cars as symbols of progress and success.

Russell Brand was wrong to tell the youth not to vote; we need to vote, and we need to vote for some serious change if we want to see it happen in our lifetime. It’s hard to believe, but until the mid-seventies the Dutch had a car-centric culture and a government who gave little or no consideration to bicycle infrastructure. The people got angry, voted for a left-wing government, and good things started to happen; laws changed, cycle paths were build, and road deaths decreased dramatically. I really don’t understand why we can’t do the same.